One remarkable property of bone is the ability to remodel itself. Every day, calcium is removed from some regions of the bone and deposited to other areas — depending on the stresses applied to them.

Repeated footstrike, which happens with long-distance running and continuous backpacking, can lead to tiny cracks in the bone, otherwise known as stress fractures. This occurs when bones are subjected to sudden and unaccustomed increases in force and loads without enough recovery time. Cells can’t resorb faster than your body can replace them.

To minimize the risk of fractures:

- Allow your bones time to adapt to new stresses via training or recovery.

- Get adequate dietary calcium.

Besides giving you strong bones and teeth, calcium is also needed for preventing muscle cramping, breaking down fat for energy, regulating the heartbeat, nerve function (if you want to feel your fingertips!), and wound healing (it allows blood to clot).

You definitely don’t want to skimp on calcium. How much do you need?

Getting Enough Calcium

The daily intake recommendations vary between countries, but the general consensus is that people are not consuming enough. In the United States, the recommended daily amount is 1,000 mg of calcium[2] Needs can fluctuate depending on age and gender.

- Menopausal women need more calcium (1200 mg per day) because their estrogen levels are lower. Estrogen assists in the deposit of calcium in the bone.

- If you sweat profusely, you’ll need more dietary calcium because it is one of the minerals lost in sweat. Replace losses by eating calcium-rich foods or supplement with a vitamin drink mix.

Since calcium absorption is greatly influenced by the type of food consumed, it helps to know which foods have the highest bioavailability.

- The absorption of calcium is about 30 percent from dairy and fortified foods (e.g., tofu, nut milk, cereals).

- The absorption of calcium from cruciferous vegetables (cabbage, broccoli, kale, and bok choy) is 50 to 60 percent while spinach is about 5 percent.

Vegans should consume plants that are high in bioavailable calcium. Many plant foods high in this mineral contain compounds such as oxalic acid and phytic acid that bind to calcium, forming an insoluble salt that prevents absorption. For instance, spinach, sweet potatoes, and beans are particularly high in oxalate. Wheat bran, beans, nuts, and seeds are high in phytate. Cooking destroys some phytates, so it is best to eat these foods heated; if eating raw, it is best to sprout or soak to reduce phytate content. The extent to which these compounds affect calcium absorption varies, but it can be more challenging to meet calcium requirements without this awareness.[3]

Vegetarian Backpacking Food Sources of Calcium

The dairy industry has spent years drilling into the minds of the collective masses that “calcium = dairy foods” so it’s perfectly natural that if you don’t consume dairy, that you might wonder if you are getting enough. Whether you can’t digest dairy because you are lactose intolerant, or simply don’t drink it, you will need some other way of getting calcium.

Luckily, calcium is naturally present in many plant foods.

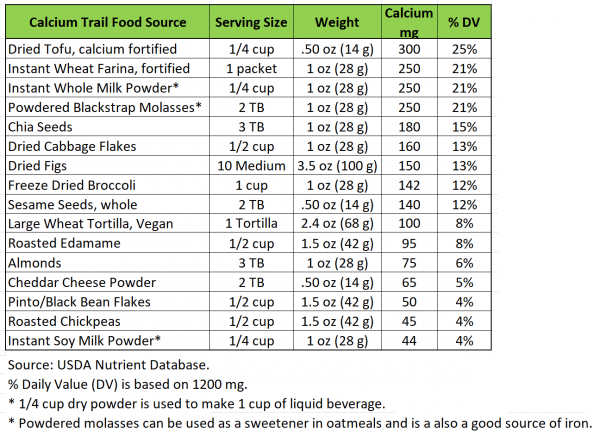

Trail Food Sources of Calcium

Calcium is retained when food is dehydrated and freeze-dried, and since calcium isn’t affected by heat, cooking doesn’t reduce the amount of calcium at all. We include dairy in this chart so you can see how it compares to plant-based sources.

Note: In establishing these DVs, the FDA doesn’t use the 1000 mg RDA value; instead, it uses the highest RDA value set by the Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) which is 1300 mg of calcium per day for adults.

Calcium-fortified foods are helpful if you don’t eat enough calcium-rich plants. For instance, when choosing non-dairy milk, e.g., almond, soy, or coconut, choose one that has been fortified with calcium; the same with tofu. Pair it with fortified cereal, such as instant wheat farina (Cream of Wheat).

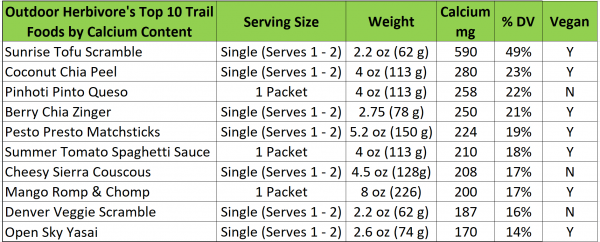

- Soy/tofu crumbles if fortified with calcium; for example, Sunrise Tofu Scramble provides 45% of your daily recommended Calcium

Calcium Cofactors

Calcium is tightly controlled and regulated by several hormones, including vitamin D, calcitonin, parathyroid hormone, estrogen (in women), and testosterone (in men), among others. Protein, magnesium, vitamin C, and vitamin E also contribute to the process of building and maintaining bone, working in conjunction with calcium. To properly absorb calcium from your food, you need some help from these cofactors:

- Vitamin D is a cofactor for calcium; you can’t absorb calcium from the gut without Vitamin D.[4]

- Vitamin K keeps calcium in your bones and out of your arteries (where it can cause calcification).[5]

Key Indicators that you have a Calcium Deficiency

If you don’t supply your body with the calcium it needs, it will respond by taking calcium from your bones and weaken them. Many people will not show symptoms immediately and will find out there is a long-term deficiency after developing a condition called osteopenia, where bone mineral density is lower than usual. This is because the body attempts to maintain calcium levels in the blood by “raiding” calcium stores in the bone. If left untreated, this decalcification of bone can develop into full-blown osteoporosis, rending the bones weaker and increasing the risk of a fracture. The good news is that weight-bearing exercise such as backpacking decreases your risk of osteoporosis because carrying a loaded pack builds a strong core.

Some people may experience the following symptoms of calcium deficiency-

- Muscle cramps. Outside of muscle overuse and dehydration, the next common triggers of muscle cramping are an inadequate intake of calcium, sodium chloride (salt), potassium, and magnesium.

- Blood is slow to clot. When you get a wound, platelets gather at the wound and attempt to block the blood flow. Calcium, vitamin K, and a protein called fibrinogen help platelets to form a clot. If your blood is lacking calcium or one of these other nutrients, it will take longer than usual for your blood to clot.

- Stress Fractures. If you experience a stress fracture, get your blood calcium level measured, and a DXA scan to assess bone mineral density.

Similar to many other nutrients, calcium does follow the general advice of “if the diet is sufficient in calcium, then supplementation is unnecessary” and excessive intakes of calcium do not promote more health benefits. In fact, if you have excess calcium, there is a risk that it will be deposited in places where it shouldn’t, like your kidneys (kidney stones) or your arteries (plaque). The Upper Intake Levels (ULs) for calcium is 2500 milligrams (mg) per day. Getting too much calcium from foods is unlikely; excess intakes are often caused by the use of calcium supplements.

Are you getting most of your trail calories from junk foods? This often results in vitamin deficiencies, a significant contributor to fatigue and illness among hikers. Here’s to staying active and healthy by eating delicious and nutrient-rich foods.

Related Posts:

References

[1] http://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/20/

[2] https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/

[3] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK56060/#

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3405161/#

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27437760/#